Several immune diseases involve inappropriate activation of immune cells called eosinophils. These include a form of allergic eczema (atopic dermatitis), a form of asthma (eosinophilic asthma), a set of gastrointestinal disorders (eosinophilic esophagitis, eosinophilic gastritis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and eosinophilic colitis), and chronic rhinosinusitis (a chronic runny nose condition).

These are not considered autoimmune diseases, because autoimmune disease involves the production of antibodies against the patient’s own tissues. Instead, eosinophilic diseases are more like exacerbated allergies or an atypical allergic response to molecules that most people do not find harmful. Unfortunately, these molecules tend to be ones encountered routinely and are present in food or the environment.

Eosinophils are a type of white blood cell. They are especially important for fighting parasitic infections, but they also participate in fighting bacteria too. In a healthy person, normally less than 1% of the white blood cells are eosinophils. If eosinophils exceed 500 per microliter of blood, then the doctor will look for a condition causing the increase. It could be an indication of an infection, a reaction to a drug, or an eosinophilic disease. Often diagnosing a tissue-specific eosinophilic disease requires taking a biopsy of the affected tissue, like biopsies of the esophagus to diagnose eosinophilic esophagitis.

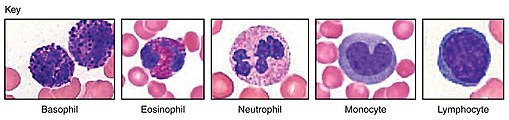

Eosinophils are identified microscopically from blood samples or tissue samples by the shape of their nuclei and by the presence of many intracellular granules, which take up a dye called eosin and make the cytoplasm of these cells appear more pink than that of other types of white cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Types of white blood cells. Credit: OpenStax College [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]. More details

Eosinophils are white blood cells with a nucleus with 2 lobes. These cells form in the bone marrow, then are released into the circulation and travel to tissues where they stay for 1-2 weeks before they eventually die. Most blood cells, except for special subsets called memory cells, are relatively short-lived, so the short lifespan for these cells is not unusual.

A particular type of T cell, called T helper 2 (TH2) cells, produce signals called cytokines to stimulate the release of eosinophils from the bone marrow. The cells follow signals called chemokines that are released from inflamed or infected tissues to their target destination.

Once in the target tissue, the cells receive additional signals that trigger them to release many different immune mediators, including pro-inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, chemokines, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins. In addition, eosinophils release protein-degrading, lipid-degrading, or RNA-degrading enzymes, cytotoxic proteins, and reactive oxygen species.

Through the release of cytokines, chemokines, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins, eosinophils play an important role in bringing other immune cells to a site of inflammation and activating those immune cells. This contributes to eliminating pathogens, damaged cells, pollutants, or irritants. Through the release of the cytotoxic proteins, enzymes, and reactive oxygen species, eosinophils themselves cause cellular damage. Sometimes these actions of eosinophils are beneficial and help eliminate a pathogen, a pathogen-infected cell, toxins, or a damaged cell. Sometimes they are harmful and cause chronic tissue damage.

In addition to producing many immune signals, eosinophils respond to many immune signals. They have receptors for chemokines, cytokines, antibodies IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG, and IgM, adhesion proteins, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Through these various receptors, eosinophils respond to infection, pollutants, tissue irritants, and allergens. Thus, they are involved in allergic responses, such as asthma, dermatitis, and sinusitis. When these cells respond excessively or abnormally to stimuli, they can cause eosinophilic diseases.

Treatment strategies vary for tissue-specific eosinophilic diseases. A common approach is to use immune-suppressing steroids, ideally applied directly to the affected tissue. For example, atopic dermatitis is often treated with a corticosteroid cream and eosinophilic esophagitis is treated with a corticosteroid dissolved in a thick liquid, like honey, which is then applied by drinking the liquid.

Although eczema and eosinophilic esophagitis are sometimes treated with the same medicines; other times the medicines used for one condition can be bad for another condition. For example, tacrolimus, which is a medicine used for eczema, is associated with causing eosinophilic esophagitis. This may relate to differences in the forms of eczema or differences in the underlying causes of the excessive eosinophil response. Thus, not all diseases associated with increased numbers of eosinophils may be treated identically and likely not all eosinophilic diseases have the same molecular or biological cause.

Eczema is fairly common, especially in children, and often spontaneously resolves. Other eosinophilic diseases are increasing in frequency and do not spontaneously resolve. Why diseases such as eosinophilic asthma and gastrointestinal eosinophilic disorders are on the rise is a mystery.

Related Resources

Atopic dermatitis (eczema). Mayo Clinic Patient Care & Health Information. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/atopic-dermatitis-eczema/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20353279 (accessed 3 September 2019)

Frequently asked questions. Cincinnati Center for Eosinophilic Disorders. https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/service/c/eosinophilic-disorders/patients/faq (accessed 3 September 2019)

What is an eosinophil? Cincinnati Center for Eosinophilic Disorders. https://www.cincinnatichildrens.org/service/c/eosinophilic-disorders/conditions/eosinophil (accessed 3 September 2019)

K. Buckland, Eosinophils. British Society for Immunology. https://www.immunology.org/public-information/bitesized-immunology/cells/eosinophils (accessed 3 September 2019)

C. N. McBrien, A. Menzies-Gow, The biology of eosinophils and their role in asthma. Frontiers in Medicine (30 June 2017) DOI: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00093 https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2017.00093

B. D. Liess, Eosinophils. Medscape (28 March 2014) https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/2090595-overview#a1 (accessed 3 September 2019)

R. D. Pesek, et al., Increasing Rates of Diagnosis, Substantial Co-Occurrence, and Variable Treatment Patterns of Eosinophilic Gastritis, Gastroenteritis, and Colitis Based on 10-Year Data Across a Multicenter Consortium. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 114, 984 -994 (2019). DOI: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000228 PubMed

Cite as: N. R. Gough, Attack of the Eosinophil. BioSerendipity (3 September 2019). https://www.bioserendipity.com/attack-of-the-eosinophil

More Articles about Immune Cells in Disease from BioSerendipity

N. R. Gough, Making Immune “Cold” Tumors Hot. BioSerendipity (31 May 2017). https://www.bioserendipity.com/2017/05/31/making-immune-cold-tumors-hot/

N. R. Gough, Fighting Cancer with the Immune System: Lessons from CAR T Cell Therapy. BioSerendipity (15 May 2017). https://www.bioserendipity.com/lessons-from-car-t-cell-therapy/

N. R. Gough, Beyond Allergies: Mast Cells Contribute to Osteoarthritis. BioSerendipity (1 June 2019) https://www.bioserendipity.com/mast-cells-contribute-to-osteoarthritis/