For 17 years I was a journal editor. I was not a researcher serving as a volunteer on a journal editorial board or a part-time academic editor also running my own lab; I was a professional editor at a broad life sciences weekly journal. Since stepping down as the Editor of the journal, I have posted and commented about issues in scholarly publishing. I have been surprised by some of the reactions from scientists and authors. It seems to me that some scientists may not understand what happens after their manuscript is submitted. It may also be that the journal where I served as Editor, Science Signaling, is an anomaly with editors that truly cared about the submitting authors and felt committed to helping get their work published in the most understandable, reproducible, and credible research article possible. This doesn’t mean that we accepted every paper. It does mean that we strove to publish research within the scope of the journal that met the journal’s criteria and satisfied the concerns of the reviewers. We provided detailed instructions for reviewers to guide the reviewers to provide reasonable evaluations intended to address missing controls, methodological problems, biased literature citation, and concerns that could change the conclusions or interpretation. However, I don’t believe that Science Signaling was so odd. I think most editors at most journals, whether they are professional editors or academic volunteer editors, are trying to do their best for the authors, the journal, and the scientific endeavor. My sense is that bad experiences with a small set of journals and publishers have led scientists to paint the entire industry with the same bad brush.

Of course, different journals have different criteria for evaluating submissions. Some depend on the profile of the journal, some depend on the scope of the journal, and some depend on the volume of submissions. High profile journals that receive many (tens of thousands) submissions tend to require that the research represents a major advance in one or more disciplines, fits within a specific article size and format, and uses the latest advances or newly developed approaches to address key questions in science. Lower profile journals can take a broader view of what fits within the journal in terms of novelty or scientific advance. However, across the journal spectrum, there are factors that limit how many submissions can be handled and proceed for in-depth peer review. Some of these limitations include the size of the editorial board or the number of staff editors evaluating the submissions and managing the peer review process. Other limitations include the pipeline for processing accepted manuscripts for publication. Consequently, most journals will reject some manuscripts either without sending them for in-depth review or after receiving reviewers’ comments even if the comments could be addressed. The time and resources have to be directed at the submissions that are most competitive and will be best for the journal. A lack of appreciation of these limitations by editors can result in unacceptable delays in managing the peer review process, decision making, and publication. These delays do not serve the authors.

When a manuscript is submitted to a journal, this creates a relationship between the journal and the authors. In this relationship, both sides should behave according to ethical standards. For journal editors, the standards have been codified by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE). COPE not only provides guidelines for ethical behavior of journal editors, but this group also provides guidelines for how to handle ethical concerns relating to authors and reviewers. One of the jobs of editors is to serve as a gatekeeper, identifying and responding to ethical breaches, to ensure the fairness and integrity of the publishing process. Authors are expected to only submit to one journal at a time, present unique work that has not been plagiarized and is not published elsewhere, declare conflicts of interest and competing interests, meet the requirements of authorship, and meet the requirements for data and materials sharing.

Editors have the responsibility of evaluating manuscripts consistently within a reasonable timeframe and providing clear information about the status of a submission and the requirements for a submission to proceed to a decision, either acceptance and publication or rejection. Many journals consider the relationship with the author to be active as long as the submission is still under consideration. In my 17 years, I never accepted a submitted manuscript without at least one round of revision. Indeed, most manuscripts went through at least 2 rounds of revision: The first round was to address issues that required additional experiments, and the second was to address issues related to the presentation.

Any manuscript that has not been rejected or accepted and published is still active with the journal. In scholarly publishing, authors are not allowed to submit their manuscript to more than one journal at a time. Most journals explicitly state this limitation and have authors acknowledge this at submission. As long as the manuscript is being actively considered at a journal, it cannot be submitted elsewhere. This includes when a manuscript is returned to the authors for revision. Such manuscript is still considered an active manuscript under consideration.

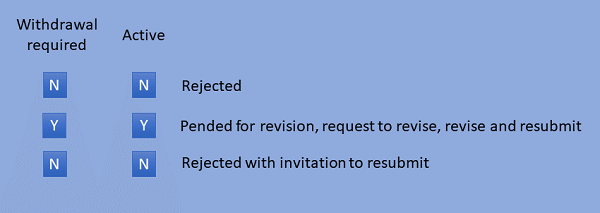

Some authors feel that this holds their manuscript “hostage,” an attitude I can understand. Indeed, to avoid holding manuscript hostage, we often rejected manuscripts that required a lot of additional experiments to be competitive and meet the journal’s and reviewers’ requirements. Sometimes, we would offer the authors an invitation to resubmit as part of the rejection. However, the authors were free to submit their manuscript elsewhere with or without addressing the reviewers’ concerns. Journal editors should not hold manuscripts hostage. Manuscripts that are far from meeting the requirements of the journal for acceptance and publication should be rejected to free the authors to submit elsewhere. Editors rejecting manuscripts because of serious technical or scientific flaws should make sure that the authors are told about these flaws so that they do not submit the flawed work to other journals.

What about the case of a manuscript that is not rejected but instead is pended for revision (also referred to as a request to revise or revise and resubmit)? Sometimes authors do not want to address the issues. If the authors feel that what is being requested is inappropriate, they should contact the editor by email and explain their position. It is entirely possible that the editor may overrule some of the issues raised by the reviewers. Authors should keep in mind that this request to revise means that the journal editors are interested in your work. They want to ultimately publish it, but they need to be sure that the work is sound methodologically, the data or findings can be reproduced, the conclusions are adequately supported, and the study meets the criteria for the journal. If the editor is not convinced that some of the issues are out of scope or inappropriate to address for the current submission, it is completely fine to decide to withdraw the manuscript from consideration at the journal. However, it is important to tell the editor that you have chosen to withdraw the manuscript, so that the record can be closed and you are not violating the rule of submitting a manuscript that is under consideration elsewhere.

While a professional editor, I experienced authors withdrawing manuscripts. The most frequent occurrence was shortly after submission. The authors had made a mistake selecting the journal (Science Signaling was one of several in the portfolio), the authors submitted the manuscript before it was ready, or the authors made a mistake on the submitted version and needed to correct it before the manuscript could be properly evaluated. Those are fine and do not create any ethical concerns. I also experienced authors withdrawing manuscripts after peer review when the manuscripts had been pended for revision. In one case, the authors withdrew the manuscript because they did not want to address the reviewers’ concerns. Unfortunately, they did not contact the editor and explain their position prior to withdrawing the manuscript. It is possible that, after discussing their explanation, we would have sided in their favor, limiting the scope of the revisions required. However, the authors did not give us the chance to hear their side before making the decision to withdraw the manuscript. This was not unethical on the part of the authors, although it may not have been in their best interests.

I also experienced authors publishing manuscripts elsewhere that were still active with Science Signaling. This is unethical. In this case, we had pended a manuscript for revision, which kept the manuscript active for the handling editor. We had a limit to how long revisions could take without some extenuating circumstance. This information was clearly conveyed in the letter sent to the author when the manuscript was sent back for revision. The manuscript was reaching that limit. When we contacted the authors, they told us that they had submitted the manuscript elsewhere and it had been accepted. We could have contacted the other journal about this breach in ethical behavior and tried to disrupt publication. We did not. However, it revealed to us that not all authors realized that a pended manuscript was still active in our journal. Thus, we modified our letters to be more explicit about when a manuscript was and was not under consideration, so that authors would be sure to notify us if they needed to withdraw a manuscript from consideration.

Another situation that I did not personally experience, as far as I know, involves using a journal to simply get peer reviewer comments without actually intending to publish the article in that journal. My opinion is that this is unethical. If you submit a manuscript to a journal, you should intend to publish the article, not just use the journal as a peer review station to see how good (or bad) the work is. A manuscript that flies through peer review without any issues being raised should not be withdrawn to submit to a different (likely higher profile) journal. A manuscript that encounters some reviewer and editorial concerns should not be withdrawn simply because revisions were requested. At least in my field of life sciences, manuscripts rarely required no changes after peer review. Thus, authors should be prepared to have some issues to address after in-depth review. If they feel that the editors and reviewers are being unreasonable, the authors should contact the editor (in email) and explain their position.

In my opinion, if the editors send a manuscript to in-depth review, there is an editorial responsibility to limit the revisions requested by the reviewers to those that address methodological issues, reproducibility, hypothesis testing, citation bias, and issues related to unsupported conclusions or overinterpretation. By sending the manuscript to in-depth review, the editors have already indicated that the study is within the journal’s scope. Issues related to meeting the journal’s criteria for publication must also be addressed. The authors also bear some responsibility in this relationship. The authors should be willing to put forth a good faith effort to address the concerns of the editors and reviewers and meet the criteria of the journal. If there are concerns that the authors feel are out of scope or unreasonable, the authors should explain their position to the editors and reviewers. Authors should not expect to only receive acceptance or rejection decisions and should realize that a request to revise means that the manuscript is still actively under consideration at the journal.

In my editorial and research experience in the cellular, molecular, and organismal life sciences, expecting a manuscript to be accepted without revision is not reasonable. However, I could be wrong and other fields may have very different frequencies of acceptance without revision. Only once in my research career did I have a manuscript accepted without additional experiments or revision. It was a manuscript rejected by the first journal without review and then accepted at the second journal after peer review. Neither journal was very high profile (Journal of Biological Chemistry and Journal of Cell Science), and this happened in 1999. Even back then, my sense was that acceptance without revision was a rare and unusual occurrence in my field. I certainly did not expect this decision and was willing to address issues raised by the reviewers and editors if there had been any.

Cover image details

Cite as: N. R. Gough, Authors and Editors, Partners not Enemies. BioSerendipity (11June 2019) https://www.bioserendipity.com/authors-and-editors,-partners-not-enemies/