Synthetic biology is the discipline of designing and then engineering artificial systems using biological components. The field of molecular biology and the ability to read the information encoded in DNA are critical to this technical discipline, which also relies on the principles of engineering, detailed knowledge of cell biology, and an understanding of chemistry. Synthetic biology can be used to alter existing biological systems to produce a desired outcome or to construct brand new systems with completely engineered properties. The applications range from developing alternative energy sources to creating diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in medicine to resolving the effects of humans on climate.

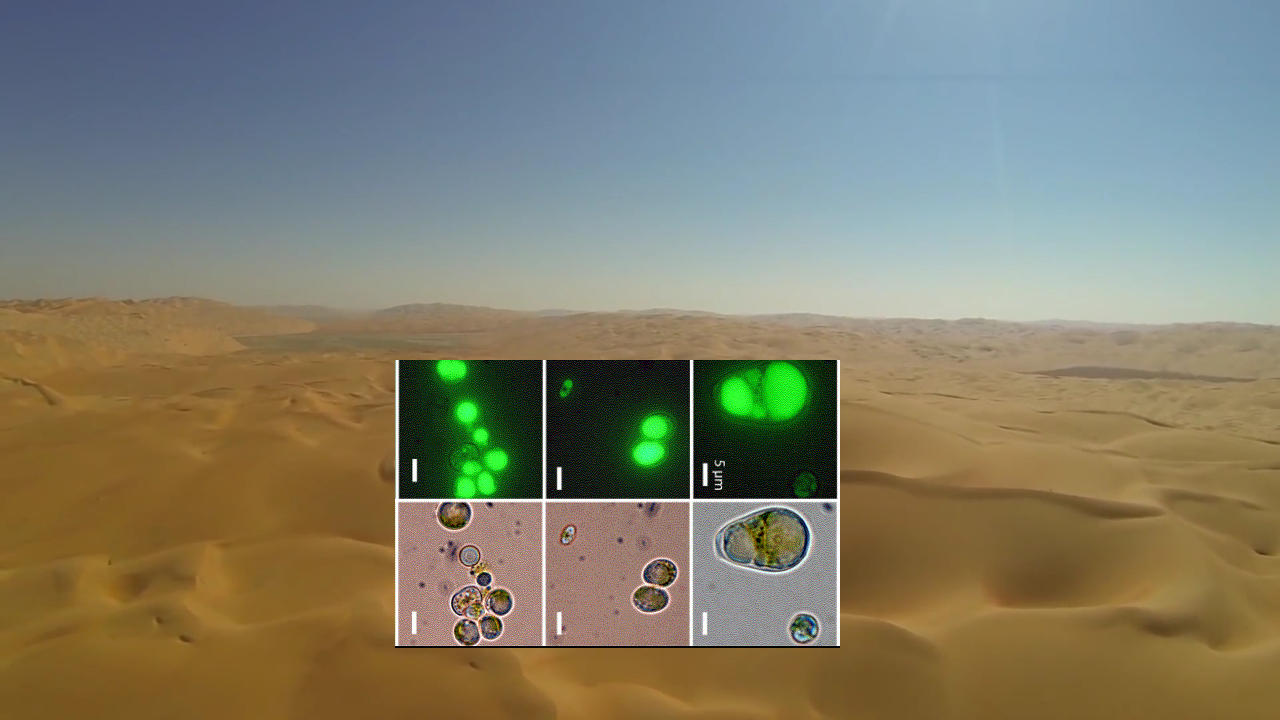

Synthetic biology benefits from basic research to provide more biology parts for the synthetic biology “toolkit.” One place to explore for new parts is in the species that can survive in extreme climates or ecological sites. Nelson and colleagues studied the green single-celled alga, Chlorodium sp. UTEX 3007, because they found that this species of algae was common throughout United Arab Emirates, a mostly desert country and had been previously identified as a lipid-producing species(Figure 1). Because this species produces the commercially useful lipid palmitic acid, it has the potential to replace palm trees as a source of this stable food oil.

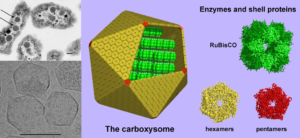

There are two types of carboxysome depending on which form of RubisCO and which carbonic anhydrase enzymes are present inside them. The protein shell of the α-carboxysome is well characterized but that of the β-carboxysome is not. Sommer and colleagues analyzed the genomes of all cyanobacteria that had been sequenced and identified 227 as having β-carboxysomes.

With this large dataset, the authors discovered 2 previously unknown types of shell proteins. Furthermore, their analysis of which shell genes were expressed together revealed the minimal requirements for building the β-carboxysome shell. Structural modeling predicted how the proteins formed the shell structure and predicted differences in the amino acids surrounding the pore through which metabolites travel (Figure 4). Pore diversity may enable the cyanobacteria to adapt to different conditions or optimize species for specific environments. These sequences are starting points for engineering carboxysomes with different properties.

Highlighted Articles

Nelson DR, Khraiwesh B, Fu W, Alseekh S, Jaiswal A, Chaiboonchoe A, Hazzouri KM, O’Connor MJ, Butterfoss GL, Drou N, Rowe JD, Harb J, Fernie AR, Gunsalus KC, Salehi-Ashtiani K, The genome and phenome of the green alga Chloroidium sp. UTEX 3007 reveal adaptive traits for desert acclimatization. eLife 6, e25783 (2017). PubMed

Sommer M, Cai F, Melnicki M, Kerfeld CA, β-Carboxysome bioinformatics: identification and evolution of new bacterial microcompartment protein gene classes and core locus constraints, J. Exp. Botany 68, 3841–3855 (2017). PubMed

Online Resources

Synthetic Biology Explained. techNyouvids https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rD5uNAMbDaQ (accessed 7 November 2017)

What is synthetic biology? Engineering Biology Research Consortium (EBRC) (accessed 7 November 2017) https://www.ebrc.org/what-is-synbio

iGEM (International Genetically Engineered Machine) http://igem.org (accessed 7 November 2017)

Cite as: N. R. Gough, Desert Green Algae and Cyanobacteria for Synthetic Biology. BioSerendipity (7 November 2017). https://www.bioserendipity.com/desert-green-algae-and-cyanobacteria-for-synthetic-biology/